|

| All those visible differences, such as clean streets and overhead power lines of city centers, make Japan so fascinating. Image credit: Riku Eskelinen: Higashimatsuyama. c b 4.0 |

I first came into contact with Japan some ten years ago by the popular Naruto anime. As the years have passed, the image about the country, its language and its culture has been developing in my mind, influenced mostly by more anime and thousand hours of Wikipedia, although I also started to study Japanese in my university a year ago.

This summer, an opportunity to visit the country cheaply and enjoyably with my girlfriend came up, thanks to a friend of mine, who is exchange studying in a Japanese university, and was able to offer us accommodation and show us around. During our two week’s stay, I had the opportunity to see many weird things, and I was quite surprised how little my image actually differed from the truth.

In this post, I’ll tell you more about the many fascinating things I saw. I will also explain how things differ from the way of life we have here in Finland. Because two weeks is a relatively short time, I wasn’t able to experience everything, and therefore this post will most likely miss some important things to see and feel.

To help the foreign readers better understand the differences between Japan and Finland, a few In Finland paragraphs explaining the Finnish customs are added to this English translation.

Tämä blogipostaus on saatavilla myös suomeksi.

Getting into the country

|

| I got my first impression of the Japanese efficiency when I was still queuing to the immigration checkpoint. Image credit: bryansblog: Immigration. c ba 2.0 |

As the airplane approached the Narita Airport, all foreign1 passengers were given two cards to fill: customs declaration and disembarkation card2. Filling both slips was mandatory, if one wished to get further than the airport lobby. The forms asked about the reason of the arrival, where one will be staying3, when one will leave the country, how much money one has with him4, and how long one’s criminal record is.

I got my first touch of the Japanese helfulness and guidance in the queue to the immigration desk. In the queue, an officer was checking that everyone had filled all the fields of the form; and another officer was guiding the people to the many desks of the immigration office. Somewhat odd was that some of the tourists − me included − were directed to the Re-entry permit holders windows to keep the queue flowing.

In order to enter the country, the passenger must give fingerprints of their index fingers and their mugshot. They are taken fast and easily by a machine on the desk. After the immigration operation, one should have a landing permission sticker and a stapled embarkation slip in their passport. Then one gets their luggage, and goes through the customs checkpoint, at which time the customs declaration card is given to the officer. After that, Japan is finally there5.

In Finland… well, to be honest, I don’t know about the customs about this. As a Finnish citizen, I can always return my own country easily and quickly without any hassle. We don’t have ”Tervetuloa kotiin” (=”Welcome home”/”おかえりなさい”) banners in our airports like they had on the Narita Airport, though.

Traveling by train

In Japan − or at least near Tokyo − the train is an easy, fast and cheap means of transportation. If one doesn’t plan to go far away from Tokyo, I’d recommend getting the PASMO travel card and credits to it from a ticket machine. The card is shown to a reader in the railway station gates both when getting in and out of the train, and the value is reduced based on the distance between the two stations.

|

| Bigger train stations have platforms for many operators. Navigating is easy, thanks to many guiding signs. |

Image credit: Riku Eskelinen: JR East -opaste. c b 4.0

The trains are operated by many companies: for example, the Yamanote Line (山手線, yamanote-sen) is operated by JR East (JR東日本, JR higashi-nihon)6, and the trains on the Tōbu Tōjō Line (東武東上線, tōbu tōjō-sen) going from Ikebukuro station (池袋駅, ikebukuro-eki) and via the station nearest to our home base, Higashimatsuyama station (東松山駅, higashi-matsuyama-eki) are driven by Tobu Railway (東武鉄道, tōbu tetsudō). PASMO is accepted on both lines, as well as on many others.

Some lines, such as the aforementioned Tōbu Tōjō, have train services with different speeds: on one service the trains stop on fewer stations than on on other. Because the cost of the trip is based on the distance between the stations, the service type does not affect the price7. For example, one can travel to Higashimatsuyama from Ikebukurosta by both the Local trains (普通, futsū) that stop on every station, and a much faster Rapid trains (快速, kaisoku).

In my short experience, the trains run very frequently, reliably and accurately, making their usage enjoyable and easy. When the train arrives, a japanese8 announcement informs the passengers and reminds them − 危ないですから (abunai desu kara), because of the dangerousness [of the arriving train] − to wait behind the yellow line. Each door of every car has its own queue (or three), which is more or less long, depending on the service type and the time of day.

After the train has stopped and the doors opened, a cruel battle of the seats begins. Kids and grown-ups, men and women all fight for the privilege of traveling seated and half-asleep. If a man gets a seat, he doesn’t give it up for women or elderly. There are, however, seats reserved for elderly, pregnant, and disabled passengers, and the status of those seats is respected.

The doors are only open for the short time the line- or station-specific chime takes to play, around half a minute. During that period, one must either get in the train, or wait for the next one. The walls and floors of the stations are decorated by warnings to not try to rush to train, which is reasonable: the trains wouldn’t be so accurate, if people tried to get to the train at the last moment9.

The train behavior of the Japanese is not unlike our Finns’ behavior in church: quietly, moderately and with cell phones on mute or off entirely. Only tourists and small children chat and play during the journey. Noisy and irritating alcoholics and teenage girls are nowhere to be seen, which seems weird for me, used to use Finnish public transportation. From what I’ve heard, however, sexual harrasment of women is somewhat often in the rush-hour trains, for which some train lines have special women-only cars.

|

| Some trains have a display showing the name of the next station. The text is usually also in English. |

Image credit: Riku Eskelinen: Seuraavana Higashimatsuyama. c b 4.0

The announcements inside the train are usually automatic, and the next station is announced in English at least once. If I remember correctly, on Tōbu Tōjō the first announcement about the next station (次は~, tsugi ha…) is also given in English, but the second, soon arriving in announcement (まもなく~, mamonaku…) is only in Japanese. On Yamanote, all announcements are given both in Japanese and in English.

One can also often hear announcements − read by either a machine or a man, and usually in Japanese only − about transfer connections and about the side the doors will next open. The passengers are also reminded to keep their phones on silent profile, or on manaa moodo (マナーモード), and to not leave their belongings behind.

If the car has an information display, the next station is displayed in it also in latin alphabet. The signs on the platforms also have the name of the station ”in English”. Thus it is difficult to miss one’s station as long as one gets on a right train and doesn’t fall asleep.

As I wrote before, when one exits the train and enters the station building, the PASMO travel card is shown to the reader again, and the display on the gate will show the cost of the journey as well as the new balance on the card. If the balance falls under one thousand yen (ca. 7 EUR), the display will show the balance on yellow background as a warning, and if the card doesn’t have enough value for the trip, one can’t go through the gates before adding more value to the card on a Fare Adjustment machine.

There are buses also. Some bus lines also accept PASMO, but the usage varies: on some lines the card is read only when getting off the bus, on some lines it is also read when getting on the bus. One gets into the bus from the middle door, and gets out from the front door.

In Finland, we only have local trains (as well as subway or trams) in the Helsinki metropolitan area. Every other major city relies complely on local buses. Both local and long-distance trains are operated by the same government-owned railway company, VR. Trains are often late or cancelled (and VR is constantly surprised by the fact that we have four seasons), and traveling is much more difficult and expensive. The buses are not that reliable, either; at least the local ones in Jyväskylä, where I live.

Cleanliness, trash and waste sorting

|

| The Japanese take trash sorting very seriously, and each type of waste has its own collect day. |

Image credit: Riku Eskelinen: Roskankeräyspiste. c b 4.0

You won’t see garbage cans on the Japanese streets. Nor will you see trash laying around, because the Japanese custom is to carry one’s trash with them to their home. Besides inside homes, trash bins can be found in grocery stores. Empty Bottles and cans can be put into separate bins often near beverage vending machines.

The Japanese don’t get to throw their garbage into one big mixed waste bin even when home. Instead, the garbage is carefully separated into burnable10, plastic, cardboard, bottle, can and unburnable trash, et cetera. Each type of garbage is collected on its own day from the same collection point on a roadside11. To make things even more difficult, there are rules on how the trash should be packaged; fortunately, the waste sorting guide and collection calendar explains this, as well.

The labels of the Japanese products have symbols telling the way the package (or part of it) is to be recycled: Plastic containers have the プラ mark12, aluminum cans have アルミ13, and so forth. One more thing about the bottles: At least in where I stayed, to throw an empty cola bottle away, one first tore off the the label14 which went to plastics, the cap went to a bag of its own, and finally the bottle was rinsed and put to a bottle bin.

I wonder if the Japanese ever have a difficult time with garbage bags piling up, when they can’t just take them out to a garbage can shelter whenever they want, like we Finns can. Especially when some types of waste are only collected infrequently − once every two weeks, in some cases. Unfortunately, I didn’t have the opportunity to see what kind of garbage chaos an ordinary Japanese home has.

In Finland, we usually throw most of our trash into mixed waste. We usually have separate recycling bins for cartons, cardboard, paper, biodegradable waste, metal and glass, but separating those is voluntary. Batteries, medicine, dangerous liquids and electric appliances must be separated and delivered to their collection points.

Beverage bottles and cans have a deposit system; we return the empty containers to the store and get the deposit back. Comparing to other countries with similar systems, the deposit value of the containers is relatively high (0.15 EUR (20 JPY) per can, and 0.10−0.40 EUR (15-55 JPY) per bottle), and therefore more than 90% of the bottles and cans are recycled this way.

Living and nichijō

|

| Vending machines selling cold beverages can be found everywhere, although they usually don’t look as good as this one. |

Image credit: Riku Eskelinen: Juoma-automaatti. c b 4.0

Although I stayed in a ”western” house − we had showers, beds and everything − the Japanese way-of-living was still there to see: the outdoor shoes were changed to indoor slippers15 when coming in, and the toilet seat had more functions than a small airplane. Comparing to mine, the kitchen was also pretty different, with two rice cookers and an electric kettle that played a tune when the water was ready.

Because the summer in Japan is ridiculously hot − temperatures raising easily over 30°C (90°F) − every home is equipped with air condition machines. From what I’ve heard, those can also be set to heat the air in the winter. I sure hope that is the case, as the one-layer windows are pretty poor insulators. There is, however, a solution for cold room air: kotatsu (炬燵), a table that has a heater built-in.

When walking outside in summer, a poor tourist used to the cold Finnish climate will sweat like crazy in t-shirt and shorts, meanwhile the local people still keep their long-sleeved shirts and normal jeans on without any noticeable problems. One can buy some relief from the drink vending machines that are everywhere. The machines offer a selection of carbonated soft drinks, water, ice tea and ice coffee; average bottle/can costing a little over 100 yen. Some of the beverages taste pretty wild, but there are also well-known western brands, such as Coca-Cola, Pepsi and Dr. Pepper, available.

I also was able to find a few ice cream vending machines, but the search for a hot beverage machine yielded no results16. There are also machines selling cigarettes and beer, but to use those, a Japanese ID card for age verification is required.

The streets and sidewalks in Japan are not only clean, but also in very good condition, although asphalt damage caused by frost heaving isn’t as big a problem in Tokyo as it is in Finland. However, the sidewalks are very narrow at best, and very often they just don’t exist. The pedestrian traffic lights work just like in Finland, although without the clicking of the ratchet or the monotone beeping of the piezo speaker. Instead, the Japanese traffic lights have much smoother sound, and some even mimic bird singing. When the lights show red man, no sound is played.

At least in Higashimatsuyama, crossing the street was easy and safe, because there was very little cars on the streets by day. The few cars that were there were ugly and box-shaped. After dark and when the driving lights are finally turned on, some ”more normal looking” cars also appeared to the streets. Perhaps the Japanese are too shy to drive their fancier cars during the daytime?

In Finland, the summer temperature is usually in between 15 and 25 degrees centigrade (60..75°F), and the Finns start to whine when the temperature raises above 25°C. All the urban legends about our insanely cold winters (and summers) are true. We usually don’t have (nor need) A/C, but we have radiators and well-insulating three-layer windows to protect us during winter.

Even though we have trash cans literally everywhere in urban areas, people still tend to throw their trash to the streets. That and the frost heaving damage we get every spring makes our streets look pretty saddening. We don’t have that much vending machines on our streets, and the toilets almost always require a 0.50-2.00 EUR (70-270 JPY) fee.

Shopping and stores

|

| The grocery items are carried to the checkout in a basket. In some stores, one can buy a plastic bag by putting a plastic slip into the basket. |

Image credit: Timothy Takemoto:

Green Communication Apprehension

c bn 2.0

The selection of a Japanese grocery store differs from a Finnish one in many ways. For instance, the fruits and vegetables are pre-packaged and therefore not weighted by the customer. They, as well as bread, are also sold in ridiculously small packages when comparing to their Finnish counterparts. For example, the biggest bag of bread comes with just eight thin slices17.

Meat is, due to lower consumption, more expensive than in Finland. On the other hand, beverages with or without alcohol (and including spirits and hard liquors) are much cheaper than ours. For most parts, comparing is made difficult by the fact that the Japanese eat food that we don’t have in Finland, and vice versa.

The items are put to a shopping basket, which is carried to the checkout station. The cashier picks the items from the basket one by one, reads them through the register, and puts them to a bought items basket. The groceries are usually paid in cash, and the bills and coins are put to a tray near the register. The cashier gives the change and the receipt to the customer’s hand, like in Finland. After getting the change, the customer picks up the basket with their purchase, and steps aside to pack them.

Visa Electron is generally not accepted, but credit cards, such as MasterCard, can be used. When paying with a credit card, the cashier will ask whether the purchase will be paid in one or in many installments. With foreign cards, the correct answer is always the former (either one-time payment or 一回, ikkai, depending on the language skills of the customer and the cashier). There is no way of failing this though, as the cash register will reject the card, if anything else than one-time payment is attempted.

With smaller, specialized, stores, one will constantly hear the sales personnel’s irasshaimase (いらっしゃいませ, ”welcome shopping”18) calls. After that, the clerk will not bother the customer further; the ”can I help you with something” queries we get in Finland are (fortunately) missing. The staff will gladly help the customer, if they ask for help, however.

In these smaller stores, the items are brought to the checkout and paid just like in Finland. These stores usually also have the tray for money. The cashier places the items into a plastic bag, and closes the bag with tape. This is to prove that the items inside are purchased from their store. The receipt is always given without a need to ask for one.

In Finland, one can choose between a shopping basket and a shopping cart. Due to greediness created by the oligopoly, long distances and the 24% VAT, everything is expensive. To add insult to injury, sugary and alcoholic items, as well as tobacco, have additional taxes in their price. Prices always include tax. At grocery store checkout, the customer unloads their basket or cart to a conveyor belt leading to the cashier, who scans the items and forwards them to another conveyer belt.

When paying in cash, the money is given from hand to hand, and one receives their change rounded to the nearest 5 cents (ca. 7 JPY). When paying with debit or credit card, the card is read with a card terminal by the customer.

The minimum age for beer and other mild alcoholic beverages is 18, and the sales person will ask the customer to show an ID if they seem to be under 30. Hard liquors are only sold in Alko, government-owned liquor store chain, and their age limit is 20.

Food and eating

|

| Ready-to-eat onigiris are sold in every grocery store, and they come in various flavors. |

Image credit: Joey Rozier: Onigiri. c bn 2.0

Eating in a Japanese restaurant is affordable: one can get their stomach full with rice or noodles with less than one thousand yen (7 EUR). With the menus just in Japanese, choosing what to eat works mostly in a trial-and-error basis. Luckily the restaurants usually have their main servings displayed in their front window.

The food itself is insanely tasty, even though it may sometimes look odd and off-putting. Most of the dishes are eaten by chopsticks. As I’m more used to the knife-and-fork combo, me eating must have seemed to be slow and painful. The Japanese habit of leaving no rice grain on the plate didn’t actually help, either19.

During the two weeks, I wasn’t of course able to taste the countless treats of the Japanese cuisine. From those that I had the pleasure to eat, I most enjoyed the tsukemen noodles (つけ麺, tsukemen) where the noodles are dipped into the soup, and also those salty onigiri rice snacks (お握り, o-nigiri) that are sold in every store. Our hostess named − without any hesitation − okonomiyaki (お好み焼き, o-konomi-yaki), kind of salty pancake, as her favourite.

Certainly one can also buy familiar junk foods, such as hamburgers. When I visited Lotteria fast food restaurant, I decided to give a teriyaki sauce flavoured burger (金のてりやきバーガー, kin-no-teriyaki baagaa, lit. gold-teriyaki-burger) a shot, and what a great decision it was: the burger was by far the best one I have had in my whole life.

In Finland, eating in a restaurant is much more expensive, although there are exceptions. It’s hard to come up with everyday dishes exclusive to Finland; our cuisine is a mix of European, Scandinavian and Russian food, with potatoes being the most common ingredient, with pasta and rice being almost as popular. Per capita, we drink almost four times more coffee than Japanese do (12 kg/person/year vs 3.3 kg/person/year), and more than anyone else. Our candy and sweets − such as salmiakki − are easily the best in the world.

Theme melodies and mascots

|

| One can come across these cute mascots in Higashimatsuyama all the time. |

Image credit: Riku Eskelinen: Ayumin ja Makkun. c b 4.0

Everything has its own tune in Japan. Besides the train station themes and kettle melodies I mentioned before, supermarkets also have their own tune, which is played in the store so much that the customer will have the song still playing in their head when they get home. Furthermore, many things, that in Finland would at most simply beep, will play a more-or-less artistic melody. For example, the school starting melody20 often heard in anime is very real part of the Japanese outdoor background soundscape.

On the other hand, one’s vision is constantly bombarded with colorful logos and mascots. For example, the mascot for Kumamoto Prefecture, Kumamon (くまモン), can be found absolutely everywhere: in food, stuffed toys, cutlery and plates, clothing, home appliances and so forth, ad nauseam. Higashimatsuyama also has its own mascot, or a pair of colorful mascots to be exact: the city is decorated with banners featuring Makkun (まっくん) and Ayumin (あゆみん) wearing their signature peony flowers and running shoes21.

In Finland, if it is absolutely necessary for a thing to have a sound, we rely on simple beeps and rings. Although some stores have a theme song to complete their brand image, those tunes are never played in the stores. Some sport teams have mascots, but that’s it. What can I say, we Finns like our environment dull, gray and silent.

Anime, manga and otaku culture

Anime and manga are commonplace in Japan. Manga books span over number of shelves in book stores − the selection is much wider than what we have for western comics in Finland. The locals also browse the manga, as well as other books, pretty freely before buying them. I noticed that in some book stores the manga books are wrapped in plastic; to prevent them from wearing out, I assume. In those cases, there usually are sample books (見本, mihon) for the most popular series, at least.

|

| Some stores also sell second-hand discs. The DVDs will always work in Finland, but with Blu-rays it’s more complicated. |

Image credit: Riku Eskelinen: Toaru Kagaku no Railgun -boksi c b 4.0

In music stores, soundtracks for anime series are well-represented, and usually one can also buy anime DVDs and Blu-rays from the same store. The discs are not very cheap, but still affordable when comparing to Play-Asia prices (incl. shipping fees), for example. Japanese DVDs are on the same region as Finnish ones, and thus will play on our players. In Blu-rays, however, Japan is in different region than us22, and the discs may not function in our home theater systems. Luckily, my experience is that some of the discs are not region-locked at all, but I advice to check the packaging carefully before buying Japanese Blu-rays.

Did I mention that anime and manga are very commonplace? Once I traveled with a One Piece themed train, which had all its ad spots (and Japanese trains have lots of them) advertising the 15th anniversary of the anime series. This went so overboard it even surprised and amused the local people.

|

| Akihabara is a must-see for all anime, manga and computer freaks. |

Image credit: Riku Eskelinen: Tervetuloa Akihabaraan. c b 4.0

Anime, manga and IT enthustiasts can find their paradise in Akihabara, Tokyo. The district is filled with huge stores with floors and floors of anime, manga, tech gadgets or games. The district is a must-see place for anyone interested in any of those. In contrast to my prejudice, most people were ordinary-looking Japanese, not morbidly obese anime pro otakus.

When I was roaming the streets of Akihabara, one thing caught my eye constantly: high school girls with flashy dresses, promoting the many maid cafés (メイド喫茶, meido kissa) of the district. With zero exaggeration, I can say that the biggest mistake I did during my whole Japan trip was to actually visit one of the meido kissas, Maidreamin.

First of all, visiting one is unbelievably expensive: with our party of three, our 45 minute stay cost us over 9000 yen (ca. 65 EUR), including a beverage of choice and an oversweet ice cream serving for each. More painful than the price were the amount of the shared feeling of shame we felt on behalf of the workers24 and the over-cuteness of the whole act − words just can’t describe them. Still, it isn’t − unlike all other weird things in Japan − something to try yourself and see. The idea in a nutshell is that the girls entertain the customers with cutesy act and, for example, dancing. It is such an overkill that I couldn’t help but feel sorry for the workers: aren’t there any better part-time job opportunities in Japan for high school girls?

In Finland, people watching anime and reading manga are often seen as weird freaks, but luckily the times are changing. Nowadays, one can even buy translated manga from a book store. Japan itself seems to be constantly ”in fashion”, and each year, many Finnish university students − like my friend − decide to go to Japan as exchange students.

Language and communication

Even though I’ve taken some Japanese courses in my University, my skill level is just too low to even survive most of the everyday situations. In my experience, English can be used just fine in Tokyo, but even as near as in Higashimatsuyama the language barrier is just too high. Let me tell you an example:

One time, I was buying food in a grocery store, and wanted to try out the automatic checkout machine. Because I could, I switched the language to English, even though using the machine would most likely have been just as easy in Japanese, thanks to the animated instruction images. Everything was nice and dandy, until it was time to check out the bananas; they don’t have a bar code so I had to select them from a menu. For some reason, the checkout machine was not willing to co-operate with me in this. A salesperson noticed my trouble and hurried to assist me. With the machine in English, the clerk could no more understand the messages, and just randomly hit buttons to get the items through. In the end, the chaos was interrupted by my friend with better Japanese skills, who kindly translated the messages back to Japanese for the salesperson.

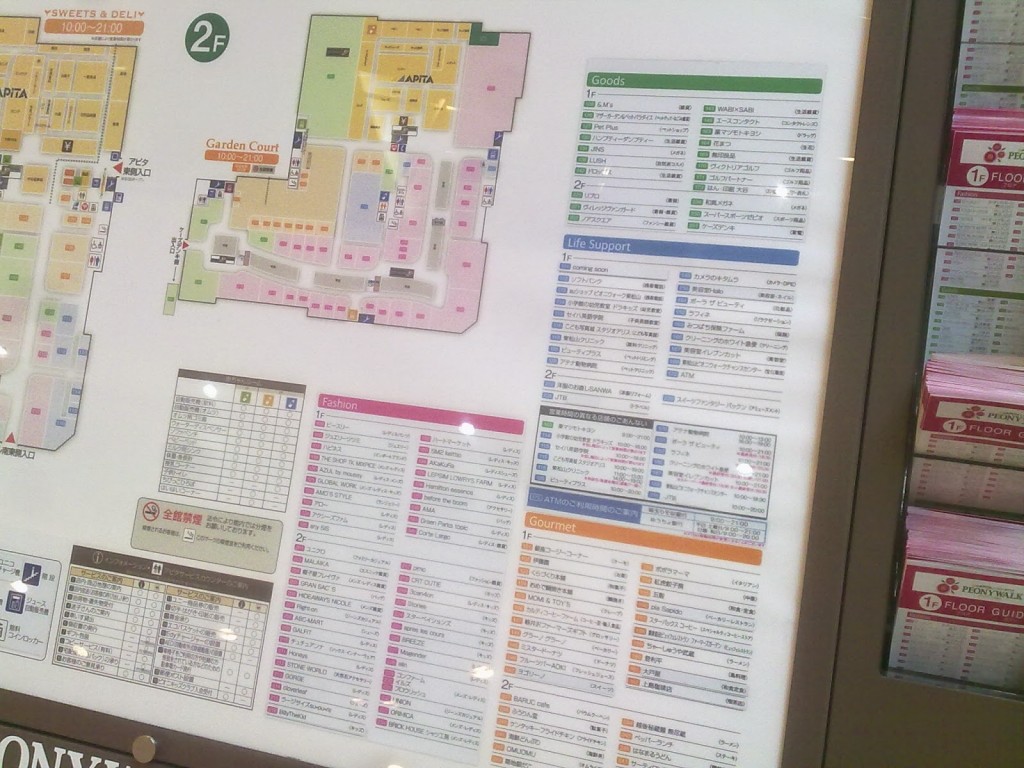

|

| The Japanese use English mostly as a special effect. In this photo, the headings are in English, but everything else is in Japanese. |

Image credit: Riku Eskelinen: Kauppakeskuksen opastetaulu. c b 4.0

Even though there were situations when I didn’t share a common language with local people, they always were doing their very best to understand and to get understood. Usually that meant either pointing and showing things, or making the decisions on behalf of the stupid westerner. This kind of let-me-help-you-then attitude felt somewhat embarrassing for a shy Finn that I am. Nevertheless, it’s one more reason to keep learning Japanese.

In Japan, many machines not only play a tune, but also speak. When an excavator vehicle turns, it plays a warning message, and the Japanese escalators warn the user about the hazards of not standing inside the yellow borders. The message is usually read in Japanese only, but for example the ATMs in post offices speak also English, if the language is switched to it.

While the English of the Japanese people is what it is, the language seems to have a certain coolness in the minds of the locals, and they love to throw English words everywhere (especially in clothing), and I did smile aloud a few times for Engrish passages. One can also see English in prohibition and warning signs: first there are lines after lines in Japanese, and below them, with small letters, the sign reads ”No smoking”.

It seems that the Japanese like their instructions well-argumented: whereas a Finnish construction site sign would read ”ei kulkua” (no entering), the Japanese version says ”あぶないからはいってはいけません”23 (abunai kara haitte ha ikemasen), ”due to the danger [of the site], entering is not allowed”.

In Finland, most people understand English well, even though they may have a hard time producing it themselves; especially in grammatically correct form. A tourist with basic English skills and with zero Finnish skills will have no problems in Finland. Swedish is the other official language in Finland, but not many Finns can use it as fluently as English; thus I’d recommend sticking with English even when one’s Swedish would be stronger than it. Studying Japanese is also possible in some universities, and many students choose to do so25.

Closing words

Japan is very different country than Finland is, by almost any standards. Still, for some reason, the place felt oddly homelike; perhaps because of the similar state of mind of the Japanese and Finnish people. I have already decided that I want to go to Japan again, for there is still so much to see and feel. If only the plane ticket didn’t cost at least 500 euro (ca. 70000 JPY), and living in Japan wasn’t as expensive as it is in Finland. Oh well, maybe it’s time for me to learn playing guitar and to play j-pop in the streets of my home town, Jyväskylä.

As a final touch, I have these points of trivia that I wasn’t able to squeeze into the article:

- Unlike in Finland, the Japanese kitchen doesn’t have a big oven. They use other equipment, such as microwave ovens, to heat food.

- Nor do they have dishbrushes or dish draining closets. The dishes are washed with a sponge and then either dried immediately or put to a draining holder on the table.

- The prices include service and tip is not given nor expected; similar to Finland. One gets their change with a accuracy of a yen (ca. 0.005 EUR), which will quickly swell the wallet of a lazy shopper with worthless 1 yen aluminum coins.

- The Japanese use the left side of stairs, and stand on that side in escalators, as well.

- One is supposed to cover their wet umbrella with a plastic wrapping offered, when entering a grocery store or a mall.

- Public toilets, which can be found e.g. on malls, are clean and they can be used free of charge.

- The beautiful and nicely trimmed riverbanks we see in anime don’t really exist. At least in Higashimatsuyama the river was surrounded with meter-high grass.

- However, ill people really do cover their mouth and nose with the famous surgical masks.

—

1) Based on the looks of the passenger

2) The card also has the embarkation form, which is stapled into the passport in the immigration checkpoint, in it.

3) I wasn’t prepared for this question. Furthermore, the field is designed for kanji characters, and getting the rōmaji address into it proved to be rather difficult.

4) For example, one is allowed to have at most one million yen (ca. 7500 EUR) in cash with them.

5) Hopefully I remembered everything correctly enough. You can tell about any mistakes in comments.

6) The logo and color theme of JR reminds very much those of VR, the railway company of Finland. Google it, if you don’t believe me.

7) There are exceptions to this rule, and some trains require one to buy a separate ticket.

8) At least I can’t recall hearing English arrival announcements besides the one time in Nippori station, when waiting for the train for Narita Airport. It is worth noting that each operator has their own announcements.

9) I did try the last-second hop-in through the closing doors once. I was successful, but the other passengers were seemingly displeased of my decision.

10) Burnable trash (燃えるゴミ, moeru gomi) is probably the closest match for Finnish mixed waste: depending on the regional regulations, paper, dirty plastic, cloths and food scraps are discarded into the burnables bin.

11) This is the normal way, but the system in use in where I stayed was a little different.

12) pura as in プラスチック, purasuchikku, plastic.

13) arumi as in アルミニウム, aruminiumu, aluminum.

14) The bottle labels have a tear-off line for easy removal.

15) These indoor sandals are so comfortable that I bought a few pairs to use back in Finland.

16) I expect that these will start to pop up when the weather starts to turn a little bit colder.

17) One can alternatively choose six somewhat thick or four fat slices with the same price.

18) There are other uses and translations, however.

19) Although I used my stupid-tourist privilege and left a few grains on the plate.

20) To be exact, the melody is the Westminster Chime, and it’s played in other parts of the world as well (not in Finland, though).

21) These features symbolize the poenies and the Three Day March (日本スリーデーマーチ, nihon-surii-dee-maachi) Higashimatsuyama is famous of.

22) Finland is in region B, Japan in region A.

23) And written with hiragana, so that the children can also understand.

24) Fun fact: In Finnish, we have a word for this feeling: myötähäpeä.

25) I have asked the Language Center of my uni for numbers on this, but they have not yet replied. I’ll update this article when more information becomes available.